Welcome to the Queering the Museum site. This site functions as an archive of the Project, our collaboration with MOHAI and the LGBTQ work being done in our field. QTM is no longer active, and we have gone each gone on to pursue new projects. We hope this archive supports the long-term grown of LGBTQ+ representation in museums.

Queer Digital Stories: Identity

Queer Digital Stories: Looking Back This post is the third in a series written by participants of our queer digital storytelling workshop. Below is the film created by Caleb Hernandez, Identity, followed by thoughts about the experience of making this film.

The Queering the Museum project was an intense four days of self-reflection. It asked that each person share a story. This request seems simple enough. What I didn’t realize was that this project would help me find a focus for my art, push me to confront my past, and serve as a reminder of the wonderful aspects of my life that I often overlook.

The process we underwent asked that we not only share our story, but to also listen and understand the experiences of the other participants. Our stories were all very unique and it was clear that there was no one Queer experience that could represent us all. This, I thought, was wonderful.

It made me interested in learning the stories of other Queer individuals. This, combined with photography, led me to create work based on Queer experience. From drag queens and their relationships with their mothers, interviewing self-identified Queer persons of all walks of life in their homes, to performing interventions on Jehovah’s Witness bibles to speak for my sister’s, father’s and my own experience in a controlling and unwavering religion.

This project pushed me to visit my hometown last summer and to speak with one of my aunts for the first time in 8 years. I was able to ask questions that I had been terrified to learn the answers to when I was younger. I learned that my father’s sexuality was fluid and he had contracted HIV and AIDS in 1993 and died of an infection the same year. This information had been kept from me since I was seven years old. The same visit led to a reconnection with one of my sisters. She found out that I was in the area and reached out to me on social media. She wanted me to know that she had a girlfriend and was going to come out to the family. She is now facing the same rejection that I had nine years ago. And I am happy she is now living her truth and has me to talk with.

I am so much more grateful for all that I have in my life. A supportive partner, a home, two wonderfully eccentric dogs, an education from one of the top 25 universities in the world, and a perspective that encompasses more than my own.

These are now part of my new story. A story I wouldn’t have been able to create without the guidance and reminders that the Queering the Museum project has afforded me. A story is worth telling and a story is worth listening to.

Caleb is a student at The University of Washington. He recently completed with a BFA in Photomedia. Having visited countless museums of all genres, Caleb understands that, not just that a Queer narrative is missing from museums, but also that it’s desperately needed. For all of the Queer youths out there that need to see a part of themselves represented and appreciated as important contributors to history.

De Facto

Queer Digital Stories: Looking Back This post is the second in a series written by participants of our queer digital storytelling workshop. Below is the film created by Mian Bond-Carvin, De Facto, followed by thoughts about the experience of making this film.

I had the great honor of being part of the very first Queering The Museum Digital Storytelling Workshop which turned out to be cathartic and transformational. Eight of us, all strangers when we met, gathered to tell our stories and came to know and have deep gratitude for one another and the interconnectedness among us and Queer people, in general. We could relate without having to explain. Those of us who are considered minorities know the immeasurable comfort in that all-too-rare occurrence.

It was clear from the beginning what story I would tell.

I am the non-biological parent of a child who was taken from me by my former partner, the child’s biological mother. She and I planned the fertilization, pregnancy, birth and our lives together. But when we broke up six-and-a-half years after the birth, my daughter was taken from me because I did not have legal standing.

Other than adoption, legal standing for non-biological parents did not exist at the time. Because of this it was necessary for me to fight for years, with the help of a brilliant team of attorneys, to change that. As a result of the legal battle to assert myself as my daughter’s parent, a law was created in Washington State to benefit and protect relationships between non-biological parents and their children. It is called the de facto parenting law.

I titled my digital story de facto. It and others created during the QTM workshop were part of an exhibit which focused on Queer histories in the Pacific Northwest. The exhibit was called Revealing Queer and ran for five months at Seattle’s MOHAI (Museum of History and Industry) in 2014.

The exhibit was validating, uplifting and created a space for us, a place for us and our stories to be seen and heard, a first for Queer people on such a large scale. Personally, the exhibit created an opportunity for my struggle to be understood and for me to be recognized and honored as someone who has positively impacted the Queer community in Washington State. I hold deep gratitude for Nicole Robert and Erin Bailey for allowing me the opportunity to be part of this historical event.

I am currently working on a feature length film entitled Self-Exiled Southern Queer.

Mian Bond-Carvin

Olympia, WA

Gender Equity and Museums

Recently Erin Bailey-Sun was asked to contribute to Gender Equity and Museums for the Incluseum, along with some truly great folks working across museums. We are so pleased with how it turned out and we want you to check it out as well!

Since the Andrew W. Mellon Report came out we have been ruminating on what the findings indicate about inclusion in museums. We also wrote a recent piece which explored some of the current issues related to museum employment and labor. The Mellon report showed that museum staff have become 60% female over the last decade (women make up about 50.9% of the US population according to the 2012 census.) The Mellon report also states that:

“… job categories, including the subset of Curators, Conservators, Educators, and Leadership, are approximately 70% or more Female.”

“By decade born, museum employees appear to be growing comparatively more Female, as shown in Figure 11. For the job category subset of Curators, Conservators, Educators and Leadership, Males remain approximately 35- 40% of museum staff regardless of decade born.”

“With close attention to equitable promotion and hiring practices for senior positions, art museums should be able…

View original post 1,519 more words

How a children’s museum got a nationally-recognized LGBTQ advocate to be an unpaid intern.

“I stumbled upon the help wanted ad while doing research for a diversity and inclusion program. The ad read, “Intern needed to support Chicago Children’s Museum’s (CCM) initiative to welcome and engage the LGBTQ community. Contribute ideas and develop activities that build awareness and sensitivity to the LGBTQ community. Photograph LGBTQ families on-site to diversify museum’s photo library.”

My first thought, a children’s museum has an initiative for the LGBTQ community? That’s brave.

My next thought: apply for the position.” – Theresa Volpe

By Theresa Volpe and Katie Slivovsky

“Sorry, can I have next week off? I’m going to The White House.” Yep, that’s what my intern, Theresa Volpe, said to me last spring. She and her family had been invited to Washington D.C. in recognition of their efforts to help pass the Marriage Equality bill in Illinois. Theresa had testified at the state capital with her partner Mercedes Santos and their two children by her side.

[Click here to read Theresa’s testimony]

Also in recognition of their advocacy, Theresa (below, left) and Mercedes, were the first* same-sex couple to be legally married in Illinois.

*Mercifully, a few same-sex couples with a terminally-ill partner were allowed to legally marry right after the bill passed in 2012.

How did this accomplished advocate come to volunteer her time for 6 months at Chicago Children’s Museum? Let her tell you.—Katie Slivovsky

In Theresa’s words:

I stumbled upon the help wanted ad while doing research for a diversity and inclusion program. The ad read, “Intern needed to support Chicago Children’s Museum’s (CCM) initiative to welcome and engage the LGBTQ community. Contribute ideas and develop activities that build awareness and sensitivity to the LGBTQ community. Photograph LGBTQ families on-site to diversify museum’s photo library.”

My first thought, a children’s museum has an initiative for the LGBTQ community? That’s brave.

My next thought: apply for the position. I saw this as an opportunity to give a voice to LGBTQ families and call attention to the need for public institutions to be more welcoming and inviting to all family structures. (Plus, I had an interest in the inner workings of museums.)

My cover letter outlined the incident which prompted my family to be involved in the fight for Marriage Equality in Illinois. I explained how our son had been hospitalized and was near death with kidney failure. My partner, Mercedes was with him. I, however, was denied access to the pediatric intensive care unit when a hospital administrator declared I was not his “real mother.” (Thankfully our son is fine now.)

Within three days of receiving the application, the HR Department at CCM called to set up an interview. I’ll admit it; I was hesitant. Did I really want to open this can of worms? Like the museum, my heart was in the right place, but my life was not. My publishing company, BrainWorx Studio, was in transition, I was already up to my eyeballs in advocacy work, and I have three young children.

WHY was I strongly considering an unpaid internship?

The answer is easy. I met the staff at CCM. If I had any doubts before walking into the interview, the staff I met would seal the deal. They wore rainbow-colored tags on their museum IDs. They practically screamed, “Ally!” Their presentation and explanation about CCM’s efforts and its policy for welcoming, engaging, and including the LGBTQ community was truly impressive.

Katie, who introduced this article and co-founded AFM in 2011, said this about CCM’s position: “As a children’s museum, our job is to do what’s best for kids. For us, it’s not political or controversial. All children deserve to see their family structures and gender expressions reflected in their communities. No one should feel invisible.” I wanted to be involved and CCM wanted me!

Shining a Light on CCM

The LGBTQ-focused committee had logged a lot of hours in the 4 years before I arrived. I looked closely at the good things that had been done before and it occurred to me that if I hadn’t had a clue about CCM’s efforts, then other families in my community probably didn’t either. I made it my goal to bring more awareness about the museum’s overall inclusiveness to Chicago’s LGBTQ community.

We started by amping up the events planned for International Family Equality Day, an event created by the Family Equality Council and celebrated around the world on the first Sunday in May. CCM had hosted the event twice before but attendance had been spotty.

We met with CCM’s Marketing staff who helped us focus on getting the media’s attention. They suggested we create an experience or activity that would make a big visual impact, resulting in a good photo op (often the difference between drawing media attention and going unnoticed.)

1,500 Yards of Ribbon

We settled on having visitors tie colored ribbons to the museum’s three-story central staircase. We would launch the program on IFED in May and continue it right through June, Pride Month in Chicago. Not only was the idea doable on the museum’s tiny budget, it created a visually captivating statement about CCM’s commitment to the diverse family structures visiting the museum.

And…it turned out to be the photo op we were looking for!

Getting Ready

I personally reached out to various LGBTQ organizations to tell them about the events and the museum’s initiative. I invited them to participate or asked them to spread the word. I was mindful of the “communities within the communities,” and sought opportunities to invite families of color by reaching out to Latino, Asian, East Asian, and black LGBTQ organizations. I also looked for ways to be inclusive to families in different income brackets.

To CCM, it was also important for families with gender expansive children or parents to feel welcome in a comfortable setting. Early on in my internship, CCM’s large signs identifying the “Boys” and “Girls” restrooms had struck me as something a child struggling with gender identity might be confused by.

Also, a transgender parent might feel more comfortable going into a non-specified bathroom. I spoke with staff at Lurie Children’s Hospital Gender & Sex Development Clinic. They recommended that prior to IFED, CCM purchase and install “All-Gender Restroom” signs on the family bathrooms–which we did. Katie wrote more about the sign here, titled “The Value of a $27.00 Sign.”

Available for $27.00 here.

Available for $27.00 here.

Connecting with LGBTQ families directly was more challenging. I drew from my own connections with the Chicagoland Rainbow Families, COLLAGE, GLSEN, and GLAAD, speaking directly to each to make sure these organizations knew CCM was welcoming to all families, including their own. The majority of the LGBTQ families attending IFEC learned about the event from one of these four organizations.

What else do LGBT families need and want from a children’s museum?

I believe LGBTQ parents appreciate the opportunity to meet each other in a family-friendly setting. Speaking from experience, my family tends to have more “mom and dad families” as acquaintances than families similar to our own. Before CCM created the LGBTQ-focused initiative in 2011, they had conducted focus groups with LGBTQ individuals and come to the same conclusion. We created the Hospitality Suite and Resource Room where LGBTQ families could meet up.

On three, free-admission evenings in May and June, we transformed the museum’s multi-purpose workshop room into a warm and welcoming place full of LGBTQ family-friendly children’s books, snacks, and music. We also had a resource table with materials about school safety, reproductive resources, support groups, organizations, gender identity clinics, and LGBTQ family-friendly children’s books.

Music to Fit the Day

I asked a children’s musician friend of mine, Stacy Buehler**, to perform on International Family Equality Day. Stacy, an early childhood educator and songwriter, wrote “Celebrate Love” which debuted at CCM!

I also invited Jason (pictured below), a transgender teen, to perform a song he had written about the importance of being yourself. I’m so inspired by his insightful lyrics. Click here to watch Jason sing “Shakily Soaring”

Jason (seated in chair) performing in CCM’s multi-purpose room. The sign outside welcomed all: “Hospitality Suite and Resource Room: Materials and Support for LGBT families and friends. ALL welcome!”

Since the museum is always family-friendly and ready to serve all people, there was no need to transform exhibit experiences but we did add a few special programs on IFEC which were available to all. Visitors could:

- Write on a 20’ long chalkboard , expressing their ideas about “What Makes a Family?” and reflecting on commonalties among families.

- Make Family Flags to share the unique make up of all families.

- Be part of a family group photo in front of the Rainbow Staircase.

- Participate in a video shoot about what makes their family special. [Click here to hear **Stacy Buehler’s original song, “Celebrate Love”:

Prepping Museum Staff

With such an obvious show of support for the LGBTQ community, we wanted all museum staff to feel comfortable talking about the museum’s initiative and handling any visitor complaints. Katie connected with all guest-facing staff and simply reminded them to handle a complaint about our rainbow staircase the same way they would handle a complaint about our “no coffee in the museum” policy: 1) calmly restate the museum’s policy, 2) keep the conversation brief (without brushing off the guest), 3) never engage in debate or add personal statements about the policy, and 4) let visitors know that completing a comment card is a solid way to ensure their voice will be heard by management. [Chicago has diverse guests from hundreds of cultures, some of which are very conservative. CCM has had more complaints about its no-coffee policy than its rainbows.]

The Outcome

Throughout May and June, nearly 80,000 visitors walked through the rainbow staircase as they moved among three floors of the museum. About 1,500 people added a ribbon themselves. Amazingly, the rainbow was complete on June 26 when the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nation-wide.

CCM’s Rainbow Staircase in 2015. A sign nearby said, “Let’s make a rainbow! We’re celebrating International Family Equality Day and Pride month. WANT TO ADD A RIBBON? Get one at the Admissions Desk. Brought to you by All Families Matter, a year-round initiative that furthers the museum’s commitment to all families by actively welcoming the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community.”

Several dozen people visited the Hospitality and Resource Room over the three evening events; a good showing but we had hoped for even more.

The overall spirit of the events was joyful, despite receiving a tiny number of negative comments, less than a handful. Staff were excited about the museum’s overt show of welcome and inclusion. We saw many happy, smiling visitors of all types explaining to their children exactly what the rainbow signifies. One teacher told Katie, “If a children’s museum can show this big sign of welcome to LGBT people, I can too. I’ve wanted to put a rainbow sticker on my classroom door; seeing this gives the courage to do it!” Yes!

The most memorable moment for me came when I saw a mother nervously fumbling through a stack of children’s books before settling on the floor with her son to read “The Tale of Two Mommies.” She continued to read one book after another. When she finished, she approached the table where I was handing out resources. I learned she came to the museum on IFED looking for information on how to deal with her family. Then she asked, “What would you do if your family was trying to turn your child against you? I told my family I’m a lesbian. They’ve been telling my son I’m a bad person.” I got the feeling I may have been one of the few—or only—other lesbian moms she had ever talked to. I told her I was sorry her family wasn’t treating her better and asked, “Do you think your child knows you love him?” “Of course! I tell him every day,” she answered. His knowing she loved him, I said, was the most important thing.

I commended her for being courageous enough to bring her son to the event. I provided her with names of organizations and an LGBTQ family playgroup. I encouraged her to seek out other LGBTQ families. When her son sees other families similar to his own, he will learn he is not the only kid with a lesbian mom and it’s okay, as long as he knows he’s loved.—Theresa Volpe

(Back to Katie:) I like to joke that before Theresa came to CCM, our eight person, interdepartmental committee consisted of a few 20-something gay people and a few 40-something straight people. NONE of us are gay parents of young children or gender expansive! You can see how essential it was to work with Theresa, a member of the demographic we were trying to reach, who is creative, organized, determined and a great communicator with a huge network of contacts. When her internship ended in June of 2015, Theresa kindly agreed to join our committee permanently as an (unpaid) advisor. On to 2016!—Katie Slivovsky

Katie Slivovsky is the Exhibit Development Director at the Chicago Children’s Museum. In 2011, she helped found CCM’s initiative to actively welcome, engage and include the LGBTQ community. Katie chairs an interdepartmental committee which assesses the inclusiveness of the museum’s environment, plans LGBTQ events, hosts International Family Equality Day each year, provides staff training, and more.

Katie Slivovsky is the Exhibit Development Director at the Chicago Children’s Museum. In 2011, she helped found CCM’s initiative to actively welcome, engage and include the LGBTQ community. Katie chairs an interdepartmental committee which assesses the inclusiveness of the museum’s environment, plans LGBTQ events, hosts International Family Equality Day each year, provides staff training, and more.

Theresa Volpe is a writer, author, editor, and co-founder, with her wife, Mercedes Santos, of BrainWorx Studio Inc., an educational publishing development company. She is an LGBT family advocate, and mother of three. She and her family were instrumental in the fight for marriage equality in Illinois. They testified before the Illinois Senate in support of the marriage equality bill and lobbied legislators in Springfield. In recognition of their efforts, Theresa and Mercedes were the first same-sex couple to be married in Illinois.

Theresa Volpe is a writer, author, editor, and co-founder, with her wife, Mercedes Santos, of BrainWorx Studio Inc., an educational publishing development company. She is an LGBT family advocate, and mother of three. She and her family were instrumental in the fight for marriage equality in Illinois. They testified before the Illinois Senate in support of the marriage equality bill and lobbied legislators in Springfield. In recognition of their efforts, Theresa and Mercedes were the first same-sex couple to be married in Illinois.

“Art AIDS America” in Review

“The exhibition is one of magnitudinal depth with transmitting hope of a reconception of who we are now and what we were then. Each piece could be considered a prayer, one of hope, memory, forgiveness and acceptance.”

By: Sarah Olivo

The Tacoma Art Museum (TAM) has curated the expansive and emotional exhibition, Art AIDS America. The mission of this exhibition is not to just show the dark, the death, and the end but what AIDS means to the living and how the human experience has and is coping with a disease that society has tried to erase. This epidemic is illustrated through artistic expression, emphasizing its ongoing existence and the current struggles. Famous names like Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar’s work meet the visitor at the beginning of three large galleries devoted to this exhibition. At once the exhibit seems overwhelming, eyes darting low and high, apparent with emotional connotation in their intent while some depictions require a closer look to truly grasp the depth of their meaning.

Upon closer look, the intersections of identity politics, what is considered “other”, and what it means to live with AIDS becomes the theme in many artists work. Glenn Ligon’s piece, “Untitled (i Am An Invisible Man)” (1993), shows intersectionalities of an identity with AIDS, race and sexuality as the face of AIDS are typically alive and well with those living within the parameters of this epidemic but those facets of identity are often ignored or overshadowed by the public’s misunderstanding and failure to look beyond AIDS. This piece speaks to not only coping with an unforgiving disease but also the idea of “otherness” that come with being black and gay in America. The late 1980s began with what the exhibit calls, “Poetic Postmodernism;” Federal laws were giving no government support to museums that were considered to be showing obscene content. This included work from gay artists depicting their struggle with AIDS. Therefore many of these pieces in the exhibition don the name, “Untitled,” for they are the manifestation of the artist perspective, meaning they could not fall under the label of “obscene content” because these works with this title are created from authentic personal experience. Through this collective title, museums maneuvered around this regimented censorship during a time of crisis in American history.

In pieces from Tino Rodriguez’ beautiful oil paintings of Dia De Los Muertos faces in loving embrace, titled “External Lovers” (2010), Rodriguez hoped to translate what it means to live with AIDS in terms of heritage. He uses traditional imagery to illustrate opposites when living in American culture, like good versus evil, horror versus humanity, and loss with presence. His stunning skulls illuminated in vibrant flowers express the triumph of love, memory, and death in the age of AIDS. Much of the exhibit promotes the authentic experience of those living with this disease and how the rest of the world might think their lives have ended, but AIDS does not mean the end and this exhibit illustrates that continuance and the possibility of growth through understanding.

This era of artistic expression the exhibition represents really began as grassroots activism and was informed by earlier feminist artists who were also working in identity politics. A piece from Judy Chicago, “Homosexual Holocaust, Study for Pink Triangle Torture,” (1989) is one example of the span of AIDS. While stereotypically being the gay mans disease, it’s effects reach the broad human experience and have infected many existences. One large brightly rainbow-colored canvas from Brett Reichman titled, “And the Spell was Broken Somewhere Over the Rainbow“(1992) is an image of swinging clocks to symbolize the relentlessness of time, it’s fleeting nature and the title as an homage to gay icon Judy Garland during the political persecution of AIDS patients. This piece was made in San Francisco where the lesbian community came together to care for their “othered” comrades. The stigma of women and children living with AIDS is alive and well. Artist Kia Labeija born HIV+ shared her intimate self portraits with TAM: living in her apartment, mourning her mother’s death, coping everyday with the disease her life has only ever known. The exhibition tries to model how prevalent this disease really is today. TAM has chosen to practice progressive museology methods by shining light on the erasure of an epidemic, of people that have died, and those that are living with AIDS. The exhibit reports that 1.2 million are living with AIDS in the U.S. and one in eight is unaware of their infection.

While the exhibition shows resilience and hope, there were moments where I had to stop to catch my breath. Specifically, Robert Sherer’s, “Sweet Williams” (2013) is made with the literal use of blood and semen, the actual physical representation of the visible transmitter of the disease. The painted flowers representing all the Williams, Wills, Billys, Bills he has known, a flower for each, sheared and laid to rest in a woven basket. I have truly never felt impacted by works like I had with these; it was physical and visceral at the same time. In artist Larry Stanton’s piece, “United.” hospital drawing with crayons on paper (1984) states, “Life is not bad. Death is not bad.”

The exhibition is one of magnitudinal depth with transmitting hope of a reconception of who we are now and what we were then. Each piece could be considered a prayer, one of hope, memory, forgiveness and acceptance. With some works listing the date of birth followed by the date of death, the fragility yet strength of human experience has never been more apparent. The exhibitions message stretches across politics, sex, religion, loss, and beauty to share the ongoing impact and how artists have become the architects of change when sharing an experience that has been made to shed so much shame, hatred, and exclusion on their existence. The exhibit opened October 3, 2015 and will close January 10, 2016. I urge you to attend, walk with a heavy and open heart through an experience many have deemed disgraceful, and leave with an understanding of the encompassing affect AIDS has had on America and humanity.

Sarah Olivo is a recent graduate from the Master of Museology program at the University of Washington. She currently works at the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience in Seattle and plans to continue to pursue opportunities of authentic storytelling, immersive experiences, and educated social change as practice.

CRG@CGP: Class, Race, Gender, Sexuality, Ability, and Museums

“My training as a historian taught me that to separate ideas of class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability from their historical contexts is to miss their true meanings—the real power that they hold in American society to shape and define people’s lives.”

By: William Walker

Each spring for the past seven years, I have taught an interdisciplinary course at the Cooperstown Graduate Program in Cooperstown, New York that explores how museums are (or should be) engaging with issues of class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability in American society and culture.[1] My students and I start by reading classic fiction and non-fiction texts—such as Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk, Richard Wright’s Uncle Tom’s Children, Anzia Yezierska’s Bread Givers, and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. These texts serve as entry points for our discussions, which tackle everything from racial violence and stereotypes to LGBTQ rights and issues of accessibility. As a public historian, I encourage my students to connect past and present while exploring the landscape of museum exhibitions, programs, and other projects that address challenging social and cultural topics.

My training as a historian taught me that to separate ideas of class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability from their historical contexts is to miss their true meanings—the real power that they hold in American society to shape and define people’s lives. Even as we discuss historical narratives, however, my students and I think about contemporary society and critically analyze current museum practice. For example, this past spring, when examining representations of lynching—in Richard Wright’s fiction, the Without Sanctuary exhibition, and the work of artist Ken Gonzales-Day—we also spent time discussing the #BlackLivesMatter movement and followed #MuseumsRespondtoFerguson on Twitter. When it works, the course design allows for seamless integration of discussions of historical interpretation and contemporary issues.

Beyond historicizing, the core goal of the course is to hone cultural competency by developing skills for interacting with many different kinds of people and critically examining the personal biases we carry. My students and I practice constructive modes of engagement, which are deeply influenced by the dialogue methods of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. Key ground rules for class discussion are:

- Use “I” statements.

- Don’t look to anyone to represent a whole group of people.

- Keep an open mind. The questions are often more important than the answers.

- Practice mindful listening.

- Engage in gentle inquiry. Ask questions to increase your understanding.

- Notice how you feel internally and how others are reacting to what you are saying or doing.[2]

In my experience, students honor the guidelines scrupulously. On rare occasions, I have had to remind them of a particular guideline or intervene—gently—in a discussion. Typically, however, we are able to get right back on track after these momentary interruptions. Although our discussions can sometimes be intense, these and other ground rules keep the level of engagement civil and constructive. These modes of engagement carry over into other areas of their work, complementing the team building strategies we emphasize throughout the curriculum, and my expectation is that students will carry these life skills forward into their careers as museum professionals.

My students and I share the common objective of analyzing and brainstorming ways museums can engage productively with issues of class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability. To support this goal, each semester we compile a list of model museum projects (like Queering the Museum) and spend time discussing them in class. Students do in-class presentation and write posts for our course blog detailing these projects. Some examples from last spring are: “Community and Collaboration in Waves of Identity: 35 Years of Archiving,” “Hide/Seek: Raising Awareness of AIDS through Art,” and “Native American Voices: Come and Listen.”

When students leave my course, I expect that they will have an array of innovative museum project ideas at their fingertips from which they can draw in the future. For example, if they are asked to contribute suggestions for an exhibition on Chinese immigration, they will be able to refer to the New-York Historical Society’s Exclusion/Inclusion exhibit or the Museum of Chinese in America’s Waves of Identity. Similarly, if they are charged with developing an exhibition on gender and sexuality, they will have the touchstones of Hide/Seek and Revealing Queer to refer to. In this way, as museum professionals, they won’t be constantly reinventing the wheel, but rather they will build on the work of their predecessors.

Each time I teach the course, my students and I start by creating a list of ways museums can engage with issues of class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability. The list is never exactly the same, but typically it looks something like this.

Museums can:

- Challenge stereotypes

- Empower subaltern groups

- Hire diverse staffs

- Collaborate with communities of color

- Explore cultural continuity and change

- Collect material culture from groups that are underrepresented in museum collections

- Run social programs

- Conduct dialogues

- Create inclusive and universally accessible spaces

- Host symposia, workshops, and conferences

- Take public stances against racism, classism, sexism, ableism, homophobia

- Gather oral histories

- Preserve historic buildings that relate to diverse audiences

- Exhibit art by artists who address class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability in their work

Understanding what museums can do, and examining how others have done some or all of these things, is the first step toward creating a new generation of museum professionals who will make twenty-first-century museums more inclusive, engaging, vibrant, and essential institutions. Ultimately, I want graduates of our program to have the skills and knowledge to be able to develop exhibitions, programs, and digital projects about some of the toughest, but also most profoundly important issues in our society. My colleagues and I recognize that a single course cannot train students to accomplish these things. Consequently, we are constantly working on ways to infuse issues of class, race, gender, sexuality, and ability across the curriculum. I would love to hear how others are tackling similar challenges.

[1] The Cooperstown Graduate Program (SUNY Oneonta) is a two-year master’s degree program in history museum studies located in Cooperstown, New York.

[2] Most of our guidelines are drawn directly from, or are variations of, the guidelines shared with me by Sarah Pharaon, Senior Director, Methodology and Practice, Sites of Conscience.

Will Walker is associate professor of history at the Cooperstown Graduate Program (SUNY Oneonta). He is the author of A Living Exhibition: The Smithsonian and the Transformation of the Universal Museum and a lead editor for History@Work, the blog of the National Council on Public History.

Omecihuatl: Reclaiming Gender through Undocumented Stories

Queer Digital Stories: Looking Back This post is the first in a series written by participants of our queer digital storytelling workshop. Below is the film created by Jacque Larrainzar, Omecihuatl, followed by thoughts about the experience of making this film.

The journey to create Omecihuatl started many years ago. I could say it started when I was very young and I was trying to makes sense of gender and sex. From a very young age I felt different, not girl, nor boy. I could not find my place in the universe. I felt lost, afraid and alone. Many years later, while I was doing research for my Queering the Museum Digital Story Project I found an interactive map of gender diverse cultures around the world. The introduction to the map said: “On nearly every continent, and for all of recorded history, thriving cultures have recognized, revered, and integrated more than two genders. Terms such as transgender and gay are strictly new constructs that assume three things: that there are only two sexes (male/female), as many as two sexualities (gay/straight), and only two genders (man/woman).” (“A Map of Gender Diverse Cultures” from Kuma Hina at PBS.org) These words confirmed something I suspected for a long time: There had been a time when my kind had a place in society, where we were part of a community and played a role. I started to look for the history of “my tribe”. I remembered a story I had heard as a child on one of the many trips I took to Teotihuacan with my grandfather. In 1992, I found a place in Mexico, Juchitan de las Mujeres, where gender and sexuality were very different from the construct imposed by Europeans on indigenous cultures.

There I learned that gender non-conforming people had been the first to die during the war of Conquest and its tales and lives erased in the name of a new male dominated religion. Many of my friends died after being tortured, others disappeared. As in many other places, their stories had been erased from History. Today, LGBTQ people all around the world face the same dangers. I have been involved in the fight for LGBT and indigenous rights in Mexico from a very young age. I was more naïve than fearless then, I had been beaten up in the streets several times for “looking like a man” but when I found out that I was on the government black list for giving shelter to women who were organizing an independent union, for providing safe sex education to transgendered women in Chiapas, and helping teachers demand a fair salary, I had no idea of what I would have to face. In December of 1994 I was held against my will, raped and tortured for three days. I was told rape and torture would “cure me” from being a pervert. It did not work, in 1997 II became the first Lesbian from Mexico to receive political asylum based on my sexual orientation. I have continued to work for the civil and human rights of my communities and I laugh when I think that the work that almost killed me in Mexico has won me many awards in the U.S. – I guess, Citizenship has its privileges.

I believe my story is one of many and these stories deserve to be kept and to be heard by others. Only then we will be able to break and overcome the cycle of violence that has taken so many lives over so many centuries.

Omecihuatl is the story of a personal journey to find my place in the Universe, an attempt to reclaim a legacy lost to me over centuries of oppression. It is a small piece of my soul that remembers and honors the lives and stories of all those, who like me, have struggled to find a place in the world and have had to fight to claim and Identity. Is a story about being undocumented, in more than one way, of coming out to find joy in being.

Omecihuatl is a story lived everyday by many others with whom I share the work to achieve justice and equality in a world where claiming to be indigenous could be more dangerous than claiming to be queer and where claiming both might mean a dead sentence. Is also a reminder to those who do not understand why we are “this way” that nothing can keep us from claiming our ancestry, our gender, our sex, our history, that we will always choose not to live in shame and to fight fear.

This little film is a small seed that I hope will bloom into a thousand flowers.

Jacque Larrainzar

QTMP Film maker and Artivists.

Queer Digital Stories: Looking Back

It is just over a year since the Revealing Queer exhibit at the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI) closed, and over two years since the QTM Digital Storytelling Workshop took place.

Pictured are our Digital Storytellers: Isis Asare, Mian Carvin, Margaret Elisabeth, Jacque Larrainzar, Fia Gibbs, Petra Davis, Caleb Hernandez and Jourdan Keith. Photo by Angelica Macklin.

The QTM project chose a digital storytelling workshop for several reasons:

- We wanted to collect the stories of queer people that would add to the historical archive.

- Digital stories are a complete narrative constructed by the subject of the story. We chose this method, as compared to oral histories, so that our subjects would have extensive control over the representation of their story.

- Digital stories are an opportunity to creatively address the lack of material artifacts. Many of our storytellers did not have photos or objects that represented the story they wished to tell. Instead, the digital storytelling model opened creative space to represent their narratives through collage, symbolic images and with voice and music.

- Through collaboration and an intense sequence of two weekends, the digital stories are produced relatively quickly.

- The final product of the digital storytelling workshop is a discrete and portable narrative that can be shared in museums, but also is an accessible historical artifact that can be viewed online and at group screenings.

- The completed digital story could be shared with QTM’s audiences, but would ultimately be owned by the story-teller. This was important in our quest to share authority and ownership of queer histories beyond the temporary partnerships that were formed in support of the Revealing Queer exhibit at MOHAI.

- Working together, rather than in isolation, the workshop model of the digital storytelling process creates opportunities to build community, even temporarily, that may have personal impacts beyond the films themselves.

The workshop was designed and facilitated by Angelica Macklin and Nicole Robert, with the help of Rebecca Sims. The films were created by eight queer storytellers, each with their own unique identities within the framework of queerness.

So, what happened?

We asked the filmmakers to share their reflections on being a participant in this workshop, now that time has passed. We wanted to know what impact the workshop itself had on their lives, as well as the personal impact of the films they produced. Several of them responded. We are excited to share these with you In the following months. Check back soon!

Queer Digital Stories: Identity

De Facto

Omecihuatl: Reclaiming Gender through Undocumented Stories

Rocking the Boat: Exhibition Methods of Storytelling the Experience of Gender & Sexuality in Museums

By: Sarah Olivo

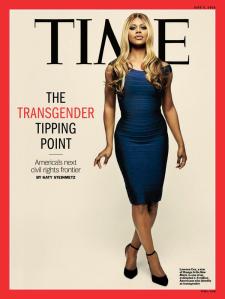

In May 2014, transgender activist and actress, Laverne Cox, graced the cover of Time Magazine heralding the “Transgender Tipping Point.” In the past year alone, we have seen athletes and celebrities question the gender binary, including the first U.S. President to ever use the word “transgender.” This is indeed a tipping point in our culture. Museums are considered the keepers of culture and their reflections of human experience tell our stories and help to better understand one another. Historically, museums have failed to tell the stories of marginalized voices, specifically of gender and sexual identity. The absence of these exhibited stories allows stereotypes and misconceptions to remain unchallenged. “Incorporating identity at the most basic level of sexual identity is an important part of realizing that we all see the world through our own lenses – and sometimes those lenses provide differing views of how it is to live in the world. This then begs the question, just where is queer in the museum world?” (Fraser, 2008, p. 7).

This research was in partial fulfillment for my graduate thesis in the Masters of Museology program at the University of Washington. The goal was to identify and describe emerging models for telling or sharing stories of female-identified and LGBTQ experience in museum exhibition. The research investigated exhibition methods of four different projects focused on historically marginalized stories based around sexual and gender identity. Data was collected through open-ended interviews with professionals directly involved in the projects and exhibits. An acknowledged self-reflexive position informed through the methodological lens of feminist standpoint theory encouraged a dialogue between “participants” instead of “subjects.” “A feminist perspective on the in-depth interview process reveals that it is more of a conversation between co-participants than a simple question and answer session” (Geiger, 2004, p.407). The identified four projects and exhibits, the professional directly involved, and examined narratives include:

- The aSHEville Museum in North Carolina, with a focus on their permanent exhibit Appalachian Women, featuring The Life of Wilma Dykeman, Asheville native who wrote many novels on feminism, womanhood, and environmentalism; exhibit developer Greta Ouziad was interviewed.

- The GLBT History Museum in San Francisco, California, the first of its kind in the United States and celebrates 100 years of queer history; executive director Paul Boneberg was interviewed.

- The exhibition Revealing Queer, a temporary exhibit at the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI) in Seattle, Washington that looked at the fifty year LGBTQ history in the Puget Sound region; museum educator Erin Bailey was interviewed.

- The Digital Storytelling Project, which profiled eight identified queer individuals to create digital stories over two workshop weekends and was a partnership with the exhibit, Revealing Queer; museum professional and academic Nicole Robert was interviewed.

During research interviews, the voice of the community was more than once described as the ocean, and the museum as a boat. Changes to museums are not the result of calm waters. But ultimately, identity-based museums can offer safe harbor and all museums can provide opportunities for inclusivity within their exhibition rotation. The results of this work will add to the growing body of research around museums as platforms for social change through authentic representation, educational storytelling, and inclusivity.

Results

This research has revealed a collection of approaches when interpreting personal stories of marginalized experience, specifically the female-identified and LGBTQ identity:

- Research as Foundation

A similar theme between all participants was research as the formidable foundation. “Making sure that information is credible and matches from one source to another is important, especially for historical exhibits” (G. Ouziad, personal communication, March 3, 2015). They also stressed the importance of acknowledging the field’s past work so to understand the history associated with this exhibition practice to provide supportive materials for future methods. - Transparency

Community involvement is a critical way to create authentic storytelling. To achieve this, recruiting for participation in the project must be done alongside initial development. This positions the museum outward and brings various identities inward, switching roles to counteract the historic institutional power imbalance. Three out of four participants indicated the importance of transparency with the community, and the necessity to thoroughly articulate how the museum functions throughout the process.

- Facilitation

The role of the museum as facilitator was highlighted by all four participants. Acting as an archival sponge that captures all the community has to offer and navigates the translation into museum quality exhibits.

- Bridge building partnerships

The findings support the value of collaborative dialogue as an informed and proactive approach to doing intersectional museum work. The importance of language is to make sure all have the same tools and definitions when constructing a narrative, acknowledging that not everyone “speaks” museum, feminist, or queer. Rebuilding partnerships to create bridges, is key to creating access. “Museums have the capability to decide what kind of experience the visitor leaves with” (Gurian, 2006, p. 150).

- Accessibility to location/space/time

Access to location, space to tell your story, and spare time to commit, are all privileges. The museum asks a great deal of those involved in what they

hope to create, therefore the museum must recognize the reciprocal relationship they have with the community. The importance of location, space, and time sheds light on the importance of temporality of one’s place in the socio-cultural context. This act of finding an alternative space, safe haven, is similar to the idea of third space feminism, which was created in response to the exclusion of women of color and indigenous voices within the feminist movement.

- Cautious not to marginalize the marginalized

The museum should strive to intentionally acknowledge those marginalized even within an already marginalized context. Every participant mentioned the challenge of lack of stories and omissions in exhibit canons. The museum professionals must listen for silences and gaps in the narrative, what cannot be articulated by objects or what has yet to be said. Both Revealing Queer and the GLBT History Museum spoke of discrepancies representing the transgender community. Whether due to severe oppression even within the LGBTQ context or just overall lack of material, the transgender experience has been one of overt oppression.

- Look ahead not just at historical data

Most exhibitions pertaining to this topic are historical cartographies. While this is necessary and should hold a place in exhibition narratives, there must also be representations of contemporary experiences. This will indicate the changing community and cultural shifts by acknowledging a current lived life outside traditional social norms.

- Valuing yourself, your story, your objects

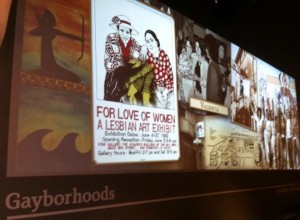

What is an exhibition without objects? The research exposes a lack of physical material for exhibitions of personal marginalized experiences. Queer history has not been well documented in museums, and what has been considered “other” has unfortunately not held value in the societal eye of the past. Erin Bailey discussed how it was difficult to find originals, as

there were mostly reproductions of flyers or meeting minutes, not the actual piece that would make an exhibition authentic. She commented that this was due to the historical lack of trust between the community and the museum. “In regards to collecting, what gets kept and what doesn’t get kept is a lot of queers in the community have the objects and multiples of them and they don’t trust anyone in the institution so they put their objects, their ephemeral objects, in multiple archives for fear that one day they will be deaccessioned” (personal communication, March 5, 2015). In addition to lack of trust issues, many of the materials may not be available. Nicole Robert discussed this discrepancy, in particular among the more marginalized communities even within LGBTQ collections, this broken access to their memorabilia could possibly be due to broken relationships with family origin, challenges with maintaining employment or home. The GLBT History Museum also acknowledged this lack of materials as due to the possibility that objects were not kept because they were thought to have no research value. Paul Boneberg spoke about how the GLBT History Museum are beginning to acquire materials for the archive by asking, “What items are we missing from our collection to tell the stories we want to tell?” (personal communication, March 2, 2015).

- Leave room to add to the archive

Missing objects, a critical feature for exhibition of personal stories of gender and sexual identity, must be collected in other nontraditional forms. Described by all four participants, doing this sort of work is a new role within the museum field, and a response to the ever-growing stories of these communities. Nicole Robert described this as the Digital Storytelling Project’s intention: “Not just to create this intervention but to have some sort of enduring impact on what gets collected [as well as] addressing some of the issues around what counts as LGBT objects” (personal communication, March 12, 2015). These digital works created an artifact that did not exist before and they tell a story that may have not been possible.

The feminist movement and LGBTQ lives are an expansive and unfolding narrative. It is wide, unmanageable, and natural, like the ocean. In order for the museum to reflect and stay relevant to their communities, they must continue to add to their archive. Whether through a social media hashtag or post-its suggesting changes, the museum must offer opportunities to add experience. Revealing Queer did this as Erin Bailey described, “We left it open for people who were coming to add on historical facts, to add on information to the labels or text that we may or may not didn’t have” (personal communication, March 5, 2015). Another method for additions to the archive is the collection of oral histories. This was mentioned by every participant and spoke about with great passion as a reliable and innovative source. Oral histories make it possible to create

linear and non-linear narratives. This encourages the present material to catch up with the past, allowing for a more current representation than the typical historical exhibition. The GLBT History Museum has engaged oral histories as a reliable method in many of their exhibitions. One example includes the enigmatic History is Now: The Dragon Fruit Project, which showcases an intergenerational historical preservation project within the queer Asian Pacific Islander (API) community in 2013. One of the labels describing the Project read, “Out of the 710 collections in the archive, no more than a handful documents queer Asian Pacific Islanders. As perhaps the first generation of openly out API queer and transgender activists approach their seventies, their history from the 1970s and 1980s may literally be lost” (GLBT History Museum). This created an intergenerational conversation on activism, coming out, love, life, and brought youth closer to their elders.

An analogy that emerged through the research interviews was the idea of the museum as a boat, which sits atop the water which is the community. Paul Boneberg mentioned this many times in context to the GLBT History Museum. “We exist on this kind of ocean of the community input” (personal communication, March 2, 2015). The boat follows the tides, and as the tides move, the museum moves with it. Waves also have the capability to shift the boat. Created by wind, the wave metaphor could be considered an outside influence. Socio-cultural motivations affect the community, thereby “moving the waters to create waves” that shift the boat. The boat, or in this case the museum, must navigate the change in the waters to stay afloat and sail successfully.

As with any research, this explorative paper and its results do not generalize to all museum exhibition practices and have their limitations. The projects were selected because they are atypical and not representative of general museum institutions or audiences, but can provide a map for institutions that are keen to weave more voices into their exhibit space.

In order for a boat to float it needs the buoyancy of water. The more museums embrace the value of community investment to their exhibits and harness the winds of change, the farther their boats will sail. Exhibiting the experiences of female-identified and LGBTQ lives holds endless opportunity to defy systematic oppression. Creating space for experiences to be shared will teach us about the past and usher in positive change for the future. The range of experience, like the ocean, will never be fully contained, but a deep respect for its voices facilitates sustainable partnerships. The museum and the community can exist in harmony, as a boat sails across water. The open water presents journeys of discovery, just like museums.

Sarah Olivo is a recent graduate from the Master of Museology program at the University of Washington. She currently works at the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience in Seattle and plans to continue to pursue opportunities of authentic storytelling, immersive experiences, and educated social change as practice.

Bibliography

Fraser, John and Joe E. Heimlich. (2008). “Where is Queer?” Museums & Social Issues: A Journal of Reflective Discourse, 3(1), p. 6-14.

Geiger, Susan. (2004). “What’s So Feminist about Women’s Oral History?” In Feminist Perspectives on Social Research, Edited by Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber and Michelle L. Yaiser, 399- 410. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gurian, Elaine. (2006). “Civilizing the Museum: The collected Writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian,” New York: Routledge.

Mertins, Donna M., John Fraser, and Joe E. Heimlich (2008). M or F? Gender, Identity and the Transformative Research Paradigm. Museums & Social Issues: A Journal of Reflective Discourse, 3(1), p. 5-160.

Scott, Joan W. (1991). “The Evidence of Experience.” Critical Inquiry, 17(4), p. 773-797.